Airport beauty consultant is not an employee

The Court of Appeal has confirmed that a beauty consultant who operated an airport concession was not an employee.

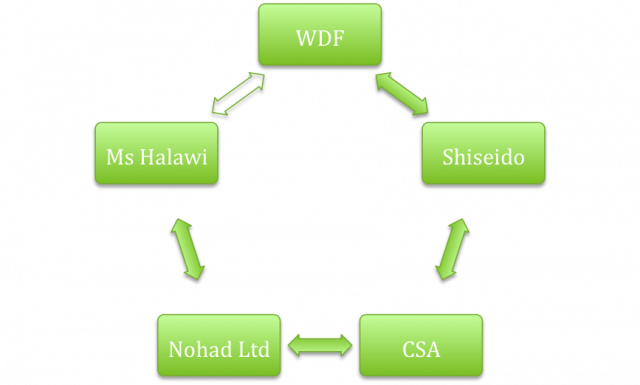

Ms Halawi ran an outlet in the duty free section of Heathrow Airport which stocked cosmetics produced by Shiseido. The arrangement by which this outlet was set up and run involved five parties:

1. WDF – responsible for management of the site in which the outlet was located; they ran all the outlets at that site, including the one run by Ms Halawi.

2. Shiseido – manufacturer of the beauty products sold at the outlet.

3. CSA – a service company who provided sales staff to sell Shiseido products.

4. Nohad Ltd – a service company set up and controlled by Ms Halawi for the provision of her services to CSA.

5. Ms Halawi – claimant.

As the outlet was located beyond the security-controlled gates, Ms Halawi required an airside pass to work there. This pass was authorised by WDF. In June 2011, WDF withdrew Ms Halawi’s pass meaning she could not longer work at the outlet.

Ms Halawi complained that WDF’s actions amounted to race and/or religious discrimination. However, in order to bring a claim against WDF she needed to show that she was an employee of WDF.

On the face of the facts, the complicated arrangement of relationships appeared to show no direct contractual relationship between Ms Halawi and WDF. Ms Halawi sought to rely on the business partner guidelines issued to her by WDF as amounting to a “contract personally to do work”. This, she argued, would make her an employee for the purposes of equality legislation. However, neither the Employment Tribunal nor the Employment Appeal Tribunal was convinced that she was indeed an employee of WDF.

At the Court of Appeal, Ms Halawi argued changed her tune and instead argued that a contract between the parties was not necessary. It sufficed that there had been a relationship of subordination between WDF and her.

The Court of Appeal disagreed. It found that the true test of whether she was an employee was to look at the level of her integration into WDF’s business. It noted that WDF did not control the way in which she carried out her work, which reflected her lack of integration into WDF. The only control WDF had was over the place where she worked.

A further strike against Ms Halawi’s status as an employee was the fact that she was not required to staff the outlet herself. If need be, she could get another person to run the outlet on her behalf. She had in fact done so in the past.

Despite its decision, the Court of Appeal was uneasy that if Ms Halawi had indeed been a victim of discrimination (an issue which had never been determined) she would be left without a means of seeking redress.

CASE Halawi v WDFG UK Ltd t/a World Duty Free, Court of Appeal, 28 October 2014